Don’t Underestimate The Reckless Stupidity of Columbus

It's that time of year, again, when we can’t agree on whether we should be celebrating Columbus or not. Here's an argument against that I don't think gets enough traction.

Much of the controversy has been debated to death, but I don’t think we’ve quite internalized, as a culture, quite what a remarkably reckless and ill-informed idea it was to sail west to Asia.

Current status of Columbus bashing

Just so I can’t be accused of ignoring other parts of the controversy: I think we can all agree that Columbus didn’t “discover” America in the sense that he was the first person to ever see it.

Yes, it is important to realize that there were already people there when he got there. But I’ve never heard anyone deny that, or met anyone older than six who was unaware of it, so it’s not a very interesting point to keep making again and again.

If I say Brian Epstein discovered The Beatles, or I tell my friends about a new restaurant I’ve discovered, I am not claiming those people or places were previously unknown to all mankind.

Let’s be adults about it, and accept that Columbus “discovered” (in one sense of the word) America for a new generation of Europeans, while also acknowledging that millions of natives and lots of other people throughout history already knew about it. Moving on.

Cruel AF

It’s far more concerning that Columbus seemed to have been pretty damned cruel. I’m generally skeptical of holding historical figures to modern-day standards–and let’s face it, a lot of people were darn callous and cruel back in the 15th century by our standards–but Columbus got called out by his contemporaries for being particularly bad.

I’m all for a day to celebrate the spirit of exploration, adventure and discovery, but don’t think we really need the violent and ruthless Columbus’ name and face on that, any more than we should observe Genghis Khan day to honor our common ancestry, or Torquemada Day to celebrate the human capacity for zeal and commitment.

If you’re going to lay claim to a whole day in our calendar, we should be entitled to hold you to a slightly higher standard than most. I don’t know exactly where to put the bar, but if there’s any doubt about whether you would clear the “don’t be a sadistic psychopath” bar, then you probably don’t qualify.

While reminders of Columbus’ cruelty and his hardly-new discovery of America is standard fare for Columbus Day, however, there is not enough talk about how ridiculously reckless and poorly thought out his journey was, or how lucky he was to find land where he did.

Columbus: 15th century tech bro

Columbus is often hailed as a great navigator. That seems a bit like calling Elizabeth Holmes a great entrepreneur. Sure, Columbus may have done some things right, but the scope of self-deception and miscalculation is so staggering that it can not be overstated.

Despite one-time popular myths, Columbus was not trying to prove to anyone that the Earth was round. Everyone whose opinion mattered in Columbus’ day knew perfectly well that the Earth wasn’t flat.

The ancient Greeks had figured out that the Earth was spherical about 2000 years earlier, in about 500 BCE — using methods and observations that today’s flat-earthers could learn a thing or two from.

In 240 BCE, the mathematician Eratosthenes, living in Egypt, calculated the circumference of the Earth — possibly accurate to within less than a percent (depending on how you convert ancient Egyptian units of distance). And Eratosthenes’ calculations had been confirmed by others (like Posidonius, in the 1st century BCE), using different methods.

Fast-forward to the 15th century, and the dawn of the Age of Exploration. The knowledge of the Earth’s shape was wide-spread, and scholars had a pretty good idea about its size.

But Columbus wasn’t exactly a scholar. He was more reminiscent of a tech bro, and he would easily have made the shortlist for a guest spot on Joe Rogan’s podcast: Largely self-taught, “doing his own research”, overly confident and out of his depth.

How big is this thing?

Now, there were admittedly a lot of misconceptions and misunderstandings going around at the time. And if Columbus had merely been “just asking questions”, trolling astronomers, and reading obscure books, it would have been easier to excuse him. It would have been annoying to his contemporaries, but not as dangerous.

But this wasn’t just theoretical. Columbus was risking his own life and that of his 86-person crew on the basis of calculations that weren’t just a little imprecise, but wildly and recklessly off.

First, the “brilliant” navigator botched his own observations, which were supposedly very carefully made, during his journeys. His numbers were way off, but he confirmed them against measurements made by famous 9th century astronomer Al-Farghani.

What he didn’t realize, however, was that Al-Farghani’s measurements were denoted in Arabic miles (ironically, the ancestor of nautical miles). Arabic miles were significantly longer than the Roman miles Columbus was working with.

Consequently, Columbus underestimated our planet’s circumference by roughly a quarter, or 10.000 kilometers.

Granted, it was hard to make accurate measurements out at sea in those days. Still … For someone who had made measurements from Britain in the north to Guinea in the south, who presumably had some idea of the distances involved, and who already had access to far more accurate calculations that were widely agreed upon, that’s not a small error to make.

How far is the Far East?

Next, Columbus cherry-picked estimates for the size of Asia.

At the time, no one knew exactly how large the continent was. They had some ancient maps based mostly on hearsay, and accounts from travelers along the Silk Road, like Marco Polo, but there was a lot of guesswork involved.

Today we know that the Eurasian continent spans about 150° from Spain to Japan, but most scholars at Columbus’ time had accepted an idea, based on cartography by 1st century polymath Ptolemy, that the “known” part of the world — from Cape Verde in the West to the furthest far east — covered about 180° on the globe.

Unfortunately, Ptolemy’s knowledge got really blurry east of the Himalayas, and ended well before he got to the Pacific. So, the large Eurasian landmass on his maps have no real east coast at all.

Now, a prudent navigator, faced with such uncertainty, might have built in some margin of safety into their calculations.

Columbus, on the other hand, found estimates that were more to his liking. In the writings of Marinus of Tyre, another 1st century Roman geographer, he found an estimate that Eurasia spanned a full 225° at the latitude of Rhodes.

Now, that still leaves a vast 135°. But then, courtesy of Marco Polo’s writings, Columbus placed Japan off the coast of China — 2–3 times further east (and much further south) than it really is. Then, east of Japan, he assumed there were more, smaller islands. And then, he corrected a bit more.

Add a bit of myth

For good measure, he thought there might be a mythical island, called Antillia, west of the Azores and, thus, between him and Japan. Not exactly wrong, considering where he ended up, but not exactly right either.

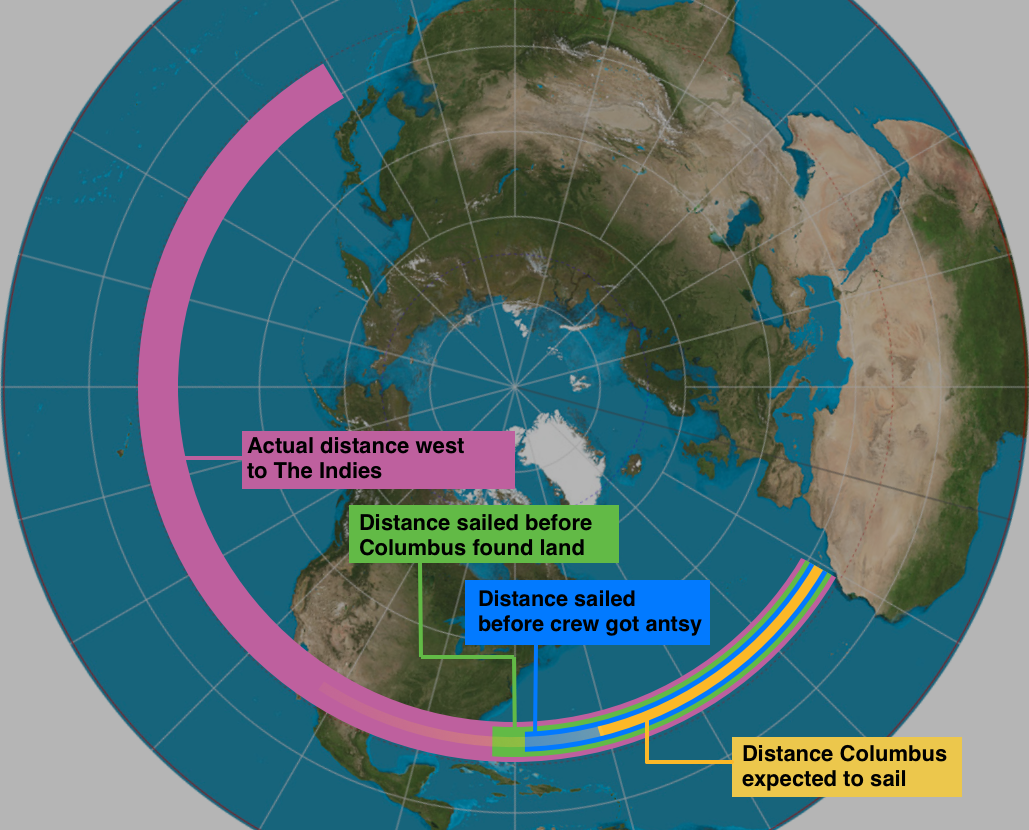

When Columbus was done massaging the numbers, his optimistic guess was that Japan was only about 2400 nautical miles away — less than 25% of the actual distance — with lots of islands on the way. And from Japan, obviously, it was just a hop, skip and a jump to China and The Indies.

No wonder his crew was feeling a bit antsy and mutinous after having travelled 3000 nautical miles without seeing land.

Columbus may have realized that was somewhat optimistic, but even with the best of will, it is hard to make Columbus’ miscalculation seem like an honest and excusable mistake. He stacked wild bets on top of poor assumptions, compounding the risk with every dubious datapoint, despite having access to better information.

Hurray for confirmation bias?

If Columbus and his crew hadn’t run into a continent they didn’t know existed, they would never have made it all the way to Asia with the ships and provisions they had.

The way Columbus worked the numbers, it was obvious that he was working backward from the conclusion he wanted. And maybe he thought he knew something…

From Viking sagas and accounts by Irish monks, to ancient Greek and Roman myths, and the story of the Malinese mansa who sailed west, there are innumerable tales of something on the far side of the Atlantic and the people who went after it.

Columbus had probably come across several such stories, plus some additional ones, invented by sailors he met along the way.

Now, none of those tales describe anything quite like the Caribbean, and certainly nothing like a vast and populous continent that could swallow Europe several times over. But it’s not unheard of that a fanciful mind can add two and two together, and get twentytwo.

It’s tempting to speculate that young Columbus had heard tales of land on the other side of the ocean and — knowing that the world was spherical — spent years looking for evidence to support what must have seemed to him like a “natural” conclusion: That the land far west was the same land as the land far east: China and The Indies.

When he arrived, then, he took that as confirmation that he was right all along. He thought Cuba was mainland China and Hispaniola was Japan, really proving his eagerness to jump to conclusions on the flimsiest evidence possible. (Really? Was this the land Marco Polo described?)

Worthy of his own day?

Self-deception, confirmation bias, and dumb luck can explain what he said and did. But it can’t excuse it. On the contrary, combined with greed and religious fervor, it made him gamble recklessly and inexcusably with people’s lives.

Columbus’ story is interesting and fun – not least as a case study in human flaws. And, for better or worse, his arrival in America is an important event in world history. As such, the story deserves to be told alongside the stories of other explorers, adventurers and pioneers.

But Columbus is neither a good role model nor a worthy hero. What are we supposed to emulate or learn from him? What’s there to honor?

Nah… If we really need a holiday in October, let’s come up with something better to celebrate.

This post is also published as a Members-Only story over at Medium.